- Home

- News & Blogs

- About Us

- What We Do

- Our Communities

- Info Centre

- Press

- Contact

- Archive 2019

- 2015 Elections: 11 new BME MP’s make history

- 70th Anniversary of the Partition of India

- Black Church Manifesto Questionnaire

- Brett Bailey: Exhibit B

- Briefing Paper: Ethnic Minorities in Politics and Public Life

- Civil Rights Leader Ratna Lachman dies

- ELLE Magazine: Young, Gifted, and Black

- External Jobs

- FeaturedVideo

- FeaturedVideo

- FeaturedVideo

- Gary Younge Book Sale

- George Osborne's budget increases racial disadvantage

- Goldsmiths Students' Union External Trustee

- International Commissioners condemn the appalling murder of Tyre Nichols

- Iqbal Wahhab OBE empowers Togo prisoners

- Job Vacancy: Head of Campaigns and Communications

- Media and Public Relations Officer for Jean Lambert MEP (full-time)

- Number 10 statement - race disparity unit

- Pathway to Success 2022

- Please donate £10 or more

- Rashan Charles had no Illegal Drugs

- Serena Williams: Black women should demand equal pay

- Thank you for your donation

- The Colour of Power 2021

- The Power of Poetry

- The UK election voter registration countdown begins now

- Volunteering roles at Community Alliance Lewisham (CAL)

The whiteness of Remembrance Day

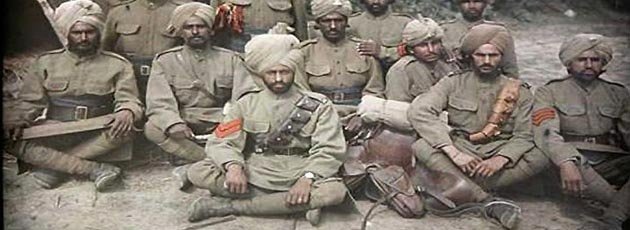

The erasure of Indian involvement in the World Wars was recently the subject of chatter surrounding the release of Christopher Nolan’s epic World War II drama, Dunkirk. The successful film failed to acknowledge the significant role Indian soldiers played in the British military and, when confronted about his authorial decisions, Nolan claimed that his approach to the film as a “pure survival story” meant that he was not focusing on the politics of the time. The film’s historical consultant, Joshua Levine, argued that “it isn’t a film’s job” to tell the complete story of Dunkirk. However, it becomes difficult to empathize with such a message when the contributions of Indians to both World Wars are so consistently left out of the story.

Remembrance has allowed for yet another chance to discuss the issue of the erasure of Indian fighters in British history. The holiday is meant as a way through which to honour and recognize those who sacrificed their lives for Britain in warfare, but there is an undeniable focus on white soldiers. Dr. Irfan Malik, who until recently had never experienced much of an interest in the World Wars, was inspired to learn more about his ancestors after a conversation with a patient concerning the participation of the Commonwealth at large during World War I. Before taking it upon himself to learn more about his own ancestors, Malik shared, he had grown up under the impression that World War I had been a purely white effort. “We weren’t taught about the Indians in school,” Malik said.

An estimated 1.3 million Indian soldiers fought in WWI, 400,000 of whom were Muslim. Approximately 2.5 million Indian soldiers fought in WWII, 600,000 of whom were Muslim. These statistics were surprising to Malik, who had always experienced trouble feeling a personal connection to Remembrance Day – until discovering that both of his great-grandfathers were Indian Muslim soldiers in the British army during WWI. According to Malik’s research, both of his great-grandfathers were from the Dulmial village in Punjab – then a part of British-occupied India – sent more soldiers to fight in WWI than any other South Asian village: 460 men.

Since learning this aspect of his family history, Malik has developed a newfound interest in Remembrance Day observances. Before, he had felt unattached, like the occasion did not include him – a feeling facilitated by the lack of inclusive education in British schools. Now, however, he has his great-grandfathers to think of whenever he fundraises for the Poppy Appeal or lays a wreath each year. Educating British people on the importance of Indian soldiers during both World Wars, to Malik, can only benefit society as a whole.

I think it reduces hate between communities and helps community cohesion. If soldiers of different faiths could fight side by side 100 years ago, why can't we get on as community groups now?"

While Nolan’s Dunkirk did not deem historically accurate representation important, the Royal British Legion has said that diversity is now a focus of its Remembrance initiatives. It reports that it has worked with local organizations, like the Punjab Heritage Association, to encourage others like Dr. Malik to research into their ancestry. Further, it plans to run a diversity-centered campaign during the 1918 Armistice centenary. Muslim communities, as well, have begun to organize their own specialized Remembrance events.

Hopefully, this marks the beginning of a trend towards Indian soldiers receiving their due honour and respect for their hand in defending Britain.

Ayan Goran